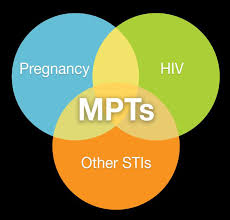

Multi-purpose prevention technologies (MPTs) are the future for female-driven sexually transmitted infection (STI) and unplanned pregnancy prevention. Although dozens of products are in the MPT development pipeline, including several at the final stages of clinical trials, progress in development has been slow, and investment paltry. In my last post, I discussed the technical and scientific barriers that are slowing down MPT research. Today I will highlight the comparable societal barriers, namely: lack of government willpower, widespread poor understanding of the depth and breadth of these health issues, and funding troubles.

Multi-purpose prevention technologies (MPTs) are the future for female-driven sexually transmitted infection (STI) and unplanned pregnancy prevention. Although dozens of products are in the MPT development pipeline, including several at the final stages of clinical trials, progress in development has been slow, and investment paltry. In my last post, I discussed the technical and scientific barriers that are slowing down MPT research. Today I will highlight the comparable societal barriers, namely: lack of government willpower, widespread poor understanding of the depth and breadth of these health issues, and funding troubles.

First, though HIV and unplanned pregnancies receive substantial attention in the fields of global health and development, other STIs tend to be much more overlooked. Fewer global health organizations conduct regular surveillance of non-HIV STIs, preventing more funding from going to their prevention. For instance, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2015 Report on global sexually transmitted infection surveillance reported an estimated 357.4 million new infections worldwide (roughly 1 million per day) of the four curable STIs—chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis and trichomoniasis. These STIs, if left untreated, can lead to complications on their own, such as pelvic inflammatory disease, miscarriage, fetal death and congenital infections. They can also increase the risk of HIV transmission during unprotected sex. This report advocates for better global STI surveillance for a multitude of reasons, including that STIs are a useful marker of unprotected sexual intercourse and could provide a warning of which populations are at risk of HIV transmission. It is important that governments begin to recognize the interconnectedness of non-HIV STIs and HIV, and combine HIV prevention with simultaneous prevention of other endemic STIs.

MPT researchers and developers also face the challenge of drumming up international willpower to back their products, many of which are still largely hypothetical and aiming to prevent diseases that would affect women far into the future. Prevention as a concept is challenging to back; it is much more lucrative for a company to develop a drug they can sell to treat HIV throughout a full life span than to develop a one-time vaccine to prevent HIV. Likewise, it is difficult to research acceptability of theoretical products. With a better understanding of MPT end-user opinions, developers would have a better understanding of which technologies have market potential, and know where they could make the most productive investments. As Amy Lin of the USAID Center for Accelerating Innovation and Impact has said, “One of the biggest challenges is that we don’t have an MPT in hand so we have to rely on analogous products or hypotheticals—but the actual experience of the product really matters.” Without reliable and robust end-user data, investors will lack assurance and motivation that their investments in MPTs will lead to widely used products.

Finally, MPTs have struggled with unique funding issues since their inception. Since they are primarily meant to be low-cost products for low-resource settings, private industry has largely shied away from funding MPTs, turned off by the lack of potential financial gain. MPT development thus far has been mainly supported by the US government (USAID and the NIH), though it is important to note that these agencies spend millions more on other areas of global health and still do not prioritize MPTs. Since MPTs lie at a crossroads of various areas within global health—including HIV/AIDS, maternal health, family planning, reproductive rights, infectious diseases, and female empowerment—they have fallen victim to the “single-issue” funding streams to which they do not narrowly fit. Many agencies and foundations that support research and programs in reproductive health only focus on one of these diverse areas. Furthermore, many hold “research mandates” and require their dollars to only be spent in restricted fields. Funders should remove these limitations and collaborate to fund singular products that address common issues across their sub-fields.

Lastly, MPT research and development cannot be sustained by the short-term funding cycles and commitments on which they currently rely. The US government agencies that provide the bulk of funding toward this research usually only provide 3-5 year grants. Due to the complicated nature of MPTs, long-term coordinated financial commitments are needed to see results from clinical trials and follow-through of successful implementation. Political priorities can change drastically every 3 to 5 years, meaning that fluctuating budgets and amounts of political support leave MPT research in a constantly precarious state.

In sum, it is critical that international governing bodies, governments, foundations and researchers begin to coordinate their research and invest long-term in MPT development. This strategy will ultimately be the most productive investment for all involved parties and result in streamlining related research into technologies that hold immense potential. European governments and private industry need to invest more money into MPTs to diversify investment streams and protect against a hostile and capricious US political climate. By working in collaboration, researchers will also bring STI prevention into the spotlight as both a pressing health issue of its own and a mirror into the spread of HIV. MPTs create a unique opportunity for various sectors to come together and tackle multiple women’s health issues through smart investments.

–Emily Nagler, Duke University 2019

Photo source: Share-Net International